Akira (1988)

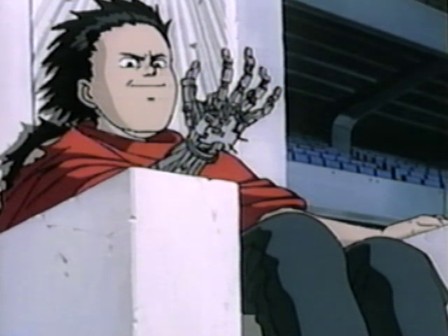

Tetsuo has made his choice.

Akira has been praised up, down, and sideways for almost forty years. I’m just an armchair Internet critic, coming in with dubious credentials and posting on free website space. Thus, I’ve put off reviewing Akira for a long time; I always lose the nerve to say, “I don’t get it,” or suggest, “maybe this is overrated.”

Now, I do get it—to a certain extent anyway. As for whether it’s overrated? Well, ahem, anyways, but the whole point of reviewing shit is you’re supposed to give your own opinion about the shit. If we were all Akira sycophants, that’d make for a pretty boring Akirasphere, wouldn’t it?

Akira, though. Yes. Kids these days will claim Naruto or One Piece as their first anime experience. Back in my day, Akira was what the kids these days, or maybe the kids before them, would call ‘The OG.’ It was the first one you heard of before anything else, the default household name in what the kids called ‘Japanimation.’ Example sentence: “Japanimation? Oh, you mean like Akira, right?”

And there was a reason for that: there was nothing else like Akira available on VHS in the U.S. In terms of animated explosions, graphic violence, and confusion, nothing. Watching gunfire shred a man apart in the street was way different than our slapsticky, censored Loony Tunes reruns. I suppose a close second might’ve been our own Heavy Metal, but that didn’t make it to home video till the mid ‘90s. Akira is what got us started bringing up the word ‘anime’ at sleepovers. Today, anime is so mainstream, you can compare how many explosions you watched that day to how many times you blinked.

I figured, if this is the moment I take on Akira, I ought to do it the proper way. I watched the original Streamline Pictures video tape release. While the tape set me back $40 on eBay, the box itself gave me a free reeducation course in how we thought back then. The spine denotes it as something called ‘Video Comics,’ which doesn’t sound as special as they thought it did. By that logic, I could have called a GoodTimes release of Mighty Mouse shorts from the IGA checkout aisle Video Comics.

What I especially love are the obnoxious pull-quotes plastered on the back. I’ve never seen that many adverbs in one place. Also, according to Joe Baltake of the Sacramento Bee, Akira “…makes ‘Blade Runner’ look like Disney World…”

And to that, I say: what’s the problem? Disney World is supposed to be fun, right? Or at least it was when I went there over twenty years ago. But again, Joe Baltake missed his own point. The Akira world of Neo-Tokyo does for Tokyo what Blade Runner did for L.A: presenting a terrible place to live by any stretch.

30 years before the story begins, an explosion erupts over Tokyo. The inspires all the world powers to empty their nuclear payloads into each other, as one would expect. In the aftermath of World War III, Japan builds a dystopian hellhole surrounding the crater called Neo-Tokyo. There’s no order in the streets, and the police don’t offer much reprieve with their riot shields and brutal gunfire.

In the middle of the chaos is Kaneda, a young teenager leading a biker gang. If you’re watching the old dub like I was, he’s also voiced by Cam Clarke. And if it was 1989 and you were used to Leonardo sounding FCC-approved, then I can imagine, “I’ll get you, you bastard!” blowing your mind.

Kaneda, his best friend Tetsuo, and their fellow gang members have a run-in with a rival set named the Clowns. The Clowns call themselves as such because they enjoy dressing in Juggalo makeup, beating down pedestrians, and throwing explosives. By contrast, we never see Kaneda’s gang commit such crimes. That makes them the good guys here.

Tetsuo crashes his bike during the battle. He is then captured by a military unit, led by a Colonel with an ‘80s mohawk and mustache. Detecting some latent psychic power inside Tetsuo, the soldiers whisk him away to a secret lab to perform experiments on him.

There are also three children at the lab, supposedly possessing this power themselves. They’re children in the sense they have the same size and mannerisms as children. But in terms of their physical appearance, they’re all shriveled up Smurf people.

Everybody, including the kids and the Colonial, starts dropping the name ‘Akira’ all over the place. This seems to be the term for this hidden power of Tetsuo’s. It also does not help those involved when Tetsuo manages to escape custody, not once, but twice. The first time, there isn’t much damage to consider. The second time? Oh, boy.

Tetsuo, who has spent his entire life being bullied, is overwhelmed when he gains more strength and abilities than he could’ve imagined. In terms us Americans can understand better, he gains great power, but none of the responsibility. He goes on a rampage through Neo-Tokyo, causing more explosions than American air missiles against Venezuelan boats. Though his central goal is solving the Akira mystery, his corruption escalates along the journey.

Meanwhile, Kaneda runs into a member of a resistance group named Kei. While her people attempt to thwart the military and rescue the psychic kids, Kei explains that Akira is a achievement several steps ahead in human evolution, as well as off limits (“Amoebas can’t build houses and atomic bombs!”)

In other words, Tetsuo is now a megalomaniac running around with the power of God. As he tears the city apart trying to find Akira, Kaneda feels it’s his responsibility to put his former best friend in the ground. He arms himself with a big laser cannon, while the Smurf kids infuse Kei with offensive psychic capabilities. The result is a whole helluva bunch more explosions, blood and guts.

Taken at face value, with the help of a few viewings, Akira is easy enough to understand. It leans on its themes—of science with no ethics, and how absolute power corrupts—more than it does telling a traditionally structured story.

An typical anime movie or season might adapt from a single light novel. Akira, on the other hand, condenses something like ten 400-page manga volumes into a 2-hour running time. Its source material told a much larger story, which as of this writing, I have not read. This is the best result they could’ve come up with.

The problem with Akira is that it also leaves so much more unexplained. It follows the logic of an OVA that crams as many characters and plot from an ongoing serial as possible, leaving the viewer to make sense of it all. That leaves more spectacle than answers, and a preference of style over substance. So…where are all these kids’ parents? Why does Kaneda have a picture of a pill on his jacket? Why are the psychic children little Benjamin Buttons? Those, and many more questions, remain unanswered during every rewatch. More exposition could’ve benefited what is already a 2-hour movie to begin with.

The realm of unanswered questions include Tetsuo’s poor girlacquaintance Kaori, whose entire role amounts to little more than enduring an attempted rape and later dying a horrible death. I suspect she played a larger role in that massive manga undertaking, but the movie’s narrative doesn’t give her anything to do except suffer.

On the other hand, the animation is beautiful. Neo-Tokyo, in all its post-apocalyptic horror, looks amazing. When all hell breaks loose in the second half, the explosions and carnage all look great. The characters move in this smooth, fluid way, to a point where I checked to see if the movie used rotoscoping (it didn’t.) Granted, sometimes there’s some weirdness to it, like how the characters speak with fish mouths that remind me of the PlayStation 2 Silent Hill games.

So that’s Akira: pretty lights, lots of violence, well-explored themes, and kind of a mess. It’s easy enough to follow, though it may require more than one viewing to digest it all. And while I get why it’s so renowned, I also empathize with those who dare to say the apple’s lost some of its shine. If I’m wrong, though, my job is done here, anywway. Go dig up and Akira and make a decision for yourself.

Final Rating: ***